How Increasing Federal Circuit Patent Scrutiny Under 35 USC 112 Impacts Applicants and Owners

How Increasing Federal Circuit Patent Scrutiny Under 35 USC 112 Impacts Applicants and Owners

By Procopio Partner Miku H. Mehta

A recent decision by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit provides new evidence of an increasing scrutiny of the claims and specifications for patents and pending applications under 35 USC 112, particularly with respect to enablement. This Federal Circuit trend, occurring simultaneously with a similar increase in focus on enablement by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, potentially impacts the survivability of many patent claims in current and future litigation. What is clear is that patent applicants must ensure their claims can withstand increased 35 USC 112 scrutiny, and patent owners must calibrate enforcement of existing portfolios appropriately. Going forward, applicants of U.S. patents would be wise to ensure claims meet these enablement requirements at the drafting stage to avoid costly enforcement headaches down the road.

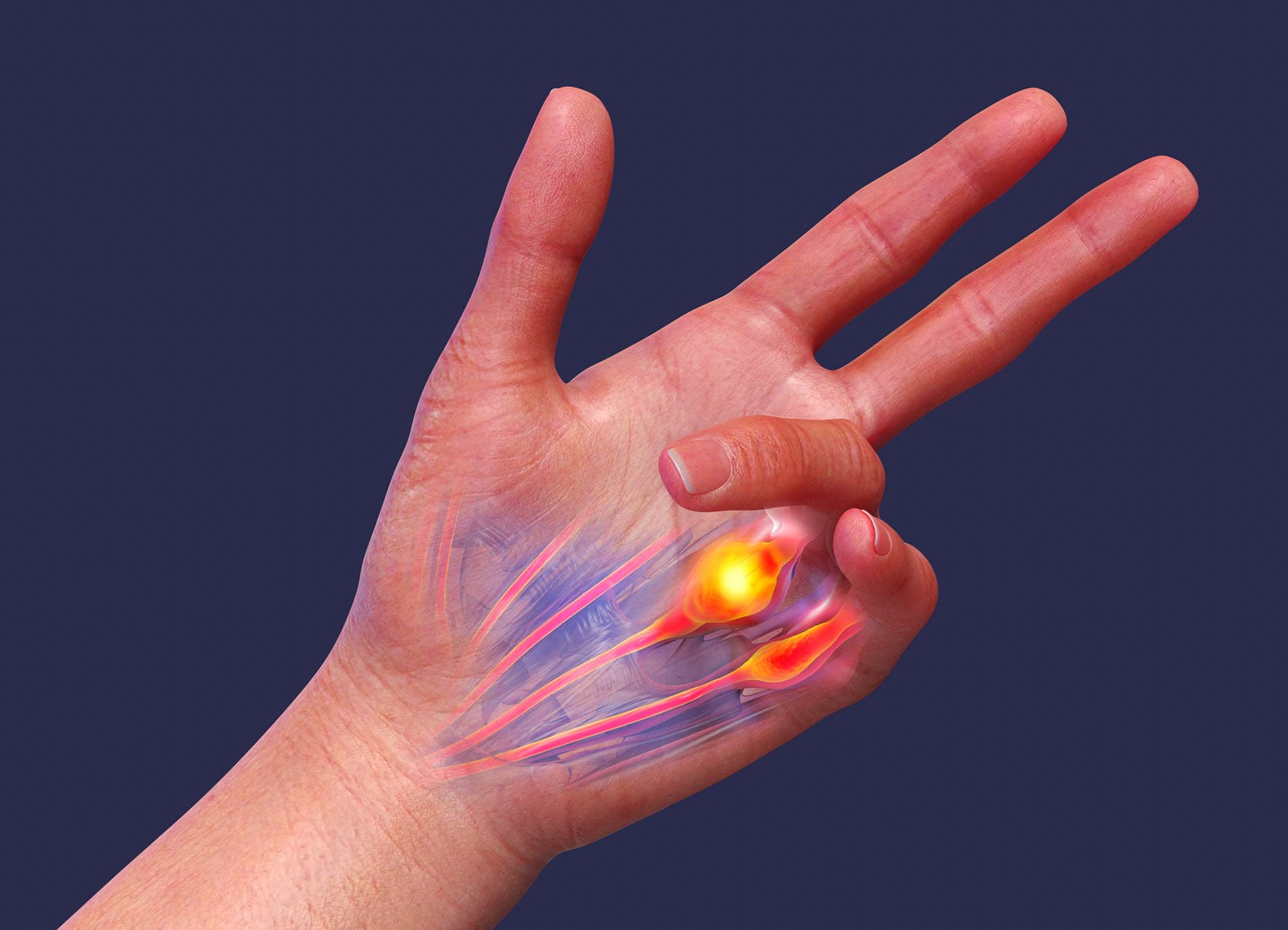

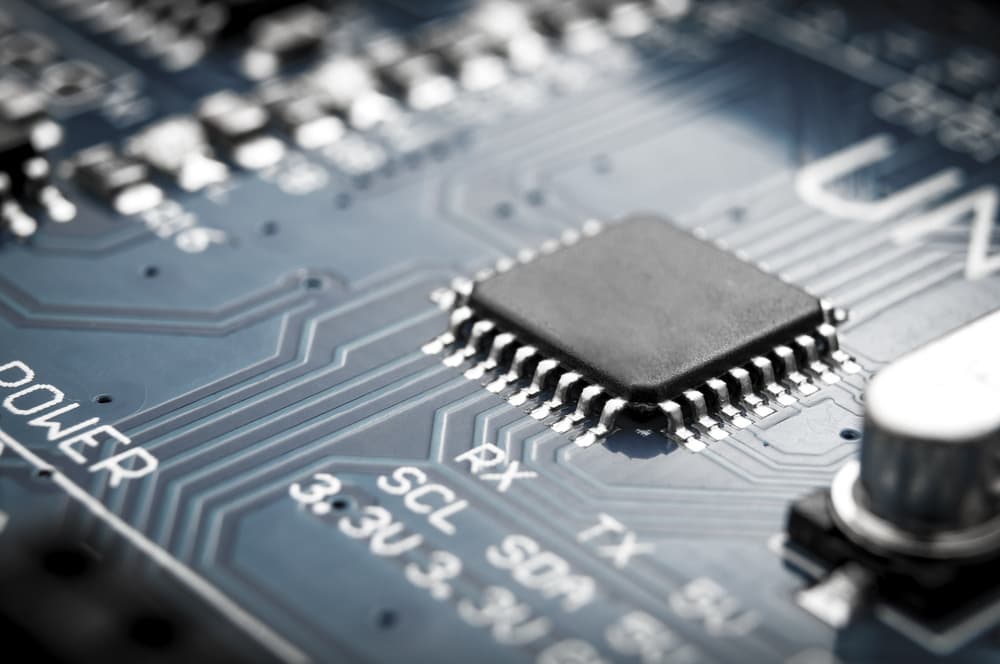

In Trustees of Boston University v. Everlight (Fed. Circ. 2018), the Federal Circuit recently revisited the relationship between the interpretation of a claim in a district court proceeding and the requirements of enablement under 35 USC 112(a). The technology at issue in this case involved US Patent No 5686738 (“’738 patent”), and related to semiconductor fabrication, more specifically the use of molecular beam epitaxy to prepare monocrystalline gallium nitride (GaN) films. According to the ‘738 patent, a non-single crystalline buffer layer (e.g., GaN) is grown on a substrate, and a growth layer (e.g., GaN and dopant material) is grown on the buffer layer.

The patentee—Trustees of Boston University or “BU”—asserted claim 19 of the ‘738 Patent against various accused product makers (i.e., defendants Everlight, Epistar and Lite-On). Claim 19 recites:

A semiconductor device comprising: a substrate, said substrate consisting of a material selected from the group consisting of (100) silicon, (111) silicon, (0001) sapphire, (11–20) sapphire, (1–102) sapphire, (111) gallium aresenide, (100) gallium aresenide, magnesium oxide, zinc oxide and silicon carbide; a non-single crystalline buffer layer, comprising a first material grown on said substrate, the first material consisting essentially of gallium nitride; and a growth layer grown on the buffer layer, the growth layer comprising gallium nitride and a first dopant material.

At the district court, a jury found that the defendants had infringed claim 19When before the Federal Circuit, the defendants argued that claim 19 was not enabled, because the specification of the ‘738 patent did not teach one skilled in the art how to make and use the claimed semiconductor device, with a monocrystalline growth layer that is grown directly on an amorphous buffer layer. The defendant also pointed out that their expert and the plaintiff’s expert both concluded that it is impossible to epitaxially grow a monocrystalline film directly on an amorphous structure.

The Federal Circuit sided with the defendants, holding that the specification does not teach one skilled in the art how to make or use a semiconductor device that is made by growing a monocrystalline layer directly grown on an amorphous layer, without undue experimentation. Because the ‘738 patent’s specification does not teach one skilled in the art how to make or use such a device without undue experimentation as of the effective filing date of the patent, the full scope of claim 19 was not enabled. The Federal Circuit also pointed out once a patentee obtains a broad claim construction, that broad claim scope must be fully enabled under 35 USC 112.

This case provides guidance to patent prosecutors as well as patent litigators:

• In the case of patent prosecutors, specifications should be drafted with detailed examples that include inventive permutations and combinations of implementations.

- The drafting should not be done solely in the context of the technical problem and its solution, but should also take into account business reasons for pursuing patent protection. For example, during the invention mining and patent drafting process, the current as well as potential future commercial embodiments should not only be envisioned, but also considered in great detail with respect to enablement. Inventors should consider how they might expect a third party to design-around or innovate an improvement on their invention.

- Claims should be drafted broadly, but not too aggressively with respect to the scope of the specification.

- During prosecution, care should be taken to avoid arguments that characterize the claim scope with respect to embodiments that are disclosed in the specification; the estoppel effect of making such arguments at the expense of narrowing claim amendments should be evaluated, as opposed to taking a “never amend” or “never argue” approach.

• For litigators, when a patent is asserted, enablement should be considered when determining claim scope for the purposes of infringement analysis, claim construction, and invalidity.

- If a patentee needs to interpret the claims so broadly that they may raise enablement issues under 35 USC 112, the patentee needs to be aware that there is a risk of the claims being invalidated based on lack of full enablement. Expert testimony cannot overcome a non-enabled specification.

Every patent owner knows that while the application process can be pricey, the cost of litigation can be far higher, claims with validity issues can adversely impact a patent portfolio in terms of stakeholder valuation, licensing value, and enforceabilty. BU v. Everlight, as well as another case that I will cover in a separate article, provides more evidence that the steps laid out above are essential for innovative patent owners to thrive in this new legal environment.

Stay up-to-date with the Procopio newsletter.

Sign Up NowMEDIA CONTACT

Patrick Ross, Senior Manager of Marketing & Communications

EmailP: 619.906.5740

EVENTS CONTACT

Suzie Jayyusi, Senior Marketing Coordinator Events Planner

EmailP: 619.525.3818

LATIN AMERICA CONTACT

Francisco Sanchez Losada, Marketing and Client Relations Manager

EmailP: 619.515.3225

ASIA PACIFIC CONTACT

Sanae Trotter, Senior Manager for Client Relations

EmailP: 650.645.9015